Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the ranks

of angels? Even if one should suddenly

take me to his heart, I would fade in the power of his

stronger existence. For beauty is nothing

but an onset of terror that we can barely stand,

and that we admire because it serenely disdains

to destroy us. Each angel is terrifying.

And so I restrain myself and swallow my dark, sobbing

call for help. Ah, whom then can we turn to,

when we are in need? Not angels, not people,

and the clever animals already know

we were never entirely at home here,

in the interpreted world. There remains for us, perhaps,

some tree on a hillside, that we might see it

every day; there remains a remembered street

and our twisted loyalty to an old habit

that likes it with us, and so stayed on and never left.

Oh, and the night, the night when the wind of the cosmos

wears on our faces -- with whom has it not lingered? Longed for,

gently disappointing night, and so hard for a single heart

to bear. Is it any easier for lovers?

Ah, each with the other only conceals their lot.

You still don't know? Cast the emptiness from your arms

into the spaces we breathe, and perhaps the birds

will feel the widening air in happier flight.

Yes, the spring times may have needed you. Many a star

was waiting for you to perceive it. There was

a wave that arose close to you long ago, or,

as you walked beneath an open window, a violin

offered itself up. That was the task assigned you.

How have you dealt with it? Did not anticipation

distract you, as if all this were announcing

the arrival of a lover? (Where would you keep her,

with all these thoughts, both great and strange, coming

and going, and often staying through the night.)

Still, when you are yearning, sing of the lovers;

the fame of their feeling is not yet immortal enough.

Those you almost envy, the deserted ones, seem

even more ardent than those whom love nurtured.

Begin, ever afresh, the praise that can never suffice;

consider that a hero lives on, so even a downfall

is only a pretext to be: his ultimate birth.

But Nature, exhausted, takes lovers back to herself,

as if she were powerless to create them again.

Have you thought enough about Gaspara Stampa

so that any young woman whose lover has gone,

with the lofty example of that great passion,

might recall her and feel: if only I were like her?

Should not these oldest sorrows of ours finally

bear some fruit? Is it not time that we lovingly free

ourselves from the ones we love, and, trembling, endure it:

as the arrow endures the bow, so that, poised for its leap,

it can be more than itself? For nowhere lets us abide.

Voices, voices. Listen, my heart, as only saints

have listened: until a mighty summons lifted them

above the ground; yet they kept kneeling,

those impossible ones, and paid the call no heed:

such was their listening. Not that you could withstand

the voice of God -- far from it. But listen to the rustling,

the uninterrupted message that shapes itself from silence.

It murmurs to you now from the youthful dead.

Whenever you went into churches in Rome

or Naples, did their fate not softly speak to you?

Or perhaps some solemn inscription gave you pause,

like the other day in Santa Maria Formosa.

What do they want of me? That I should quietly

dispel the sense of injustice that sometimes hinders,

a little, the free movement of their spirits.

Of course, it is strange to dwell on the Earth no more,

to practice no more the barely learned skills;

not to give to roses and other such promising things

the meanings that belong to a human future.

To be no more everything that one was,

in endlessly anxious hands, and even to put aside

one's own name like a broken plaything.

Strange to no longer wish one's wishes. Strange,

to see everything once connected fluttering

loosely in space. And to be dead is arduous

and full of catching up, till one gradually

senses a little eternity. -- But the living all make

the mistake of drawing distinctions too sharply.

Angels (they say) often cannot tell whether they move

among the living or the dead. The eternal tide

surges forever through both realms, bearing all ages

within it, and drowns out both in its flow.

In the end, they need us no more, those taken early:

one weans oneself gently from earthly things, as one was

tenderly weaned from a mother's breasts. But we, who need

such great mysteries and for whom blessed progress

so often springs from grief -- could we exist with them?

Is the story in vain how once, in the mourning for Linos,

the daring first music broke through the numb and barren air;

only then, in the startled space from which a nearly godlike young man

had suddenly departed forever, did emptiness feel

the vibration that now enthralls us and consoles and helps.

Rainer Maria Rilke, 'Die Erste Elegie' from Duineser Elegien, 1912-1922; translation by Frank Beck.

A century on, this is a fresh attempt to render the first of Rilke's Duino Elegies in English, using the vocabulary and diction of the poet's contemporaries. To do so, I have consulted concordances of the works of E.M. Forster, Henry James, Edith Wharton, and Virginia Woolf.

While German and English employ very different sentence structures, I have tried to echo Rilke's cadences wherever possible. And I have attempted to capture the subtle alterations in tone, as the poem moves effortlessly from the intimate to the oracular.

There is a long tradition of translating Rilke into English. From the many versions available, I found those of Jessie Lemont, Nora Wydenbruck (a native speaker of German), and Ruth Speirs especially helpful when the meaning of one of Rilke's constructions eluded me.

As the Duino Elegies enter their second century, it is easy to see why they are among the most cherished works of modern literature.

Above: 'Portrait of the poet Rainer Maria Rilke' (detail) by Leonid Osipovich Pasternak, 1928.

|

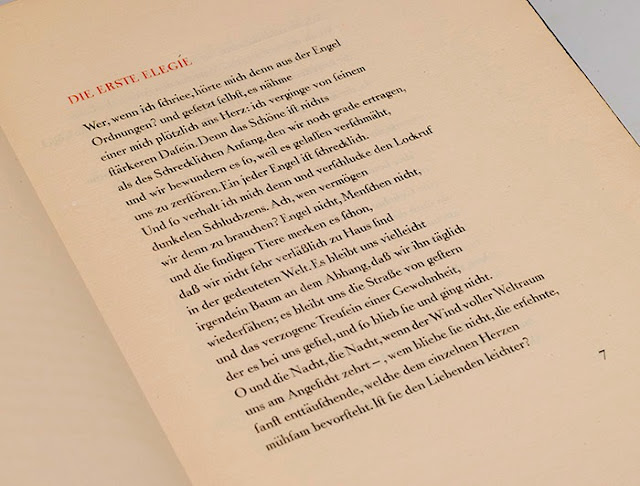

| Cover of the first edition, published by Insel Verlag in October 1923 |

I am imagining with such fabulous clarity how you must look now: just as in those days long, long ago, when the brightness in your eyes and your cheerful stance would sometimes make one imagine a boy: and whichever hope moved you then, whatever it was that you were asking of life, absolutely and intensely, as your only need and necessity -- is now as if fulfilled.

Lou Andreas-Salomé, in a letter to Rilke on February 16, 1922, on receiving the last three Elegies by mail. (Translation by Edward Snow and Michael Winkler)

|

| First page of the First Elegy in the original German edition |

.jpeg)